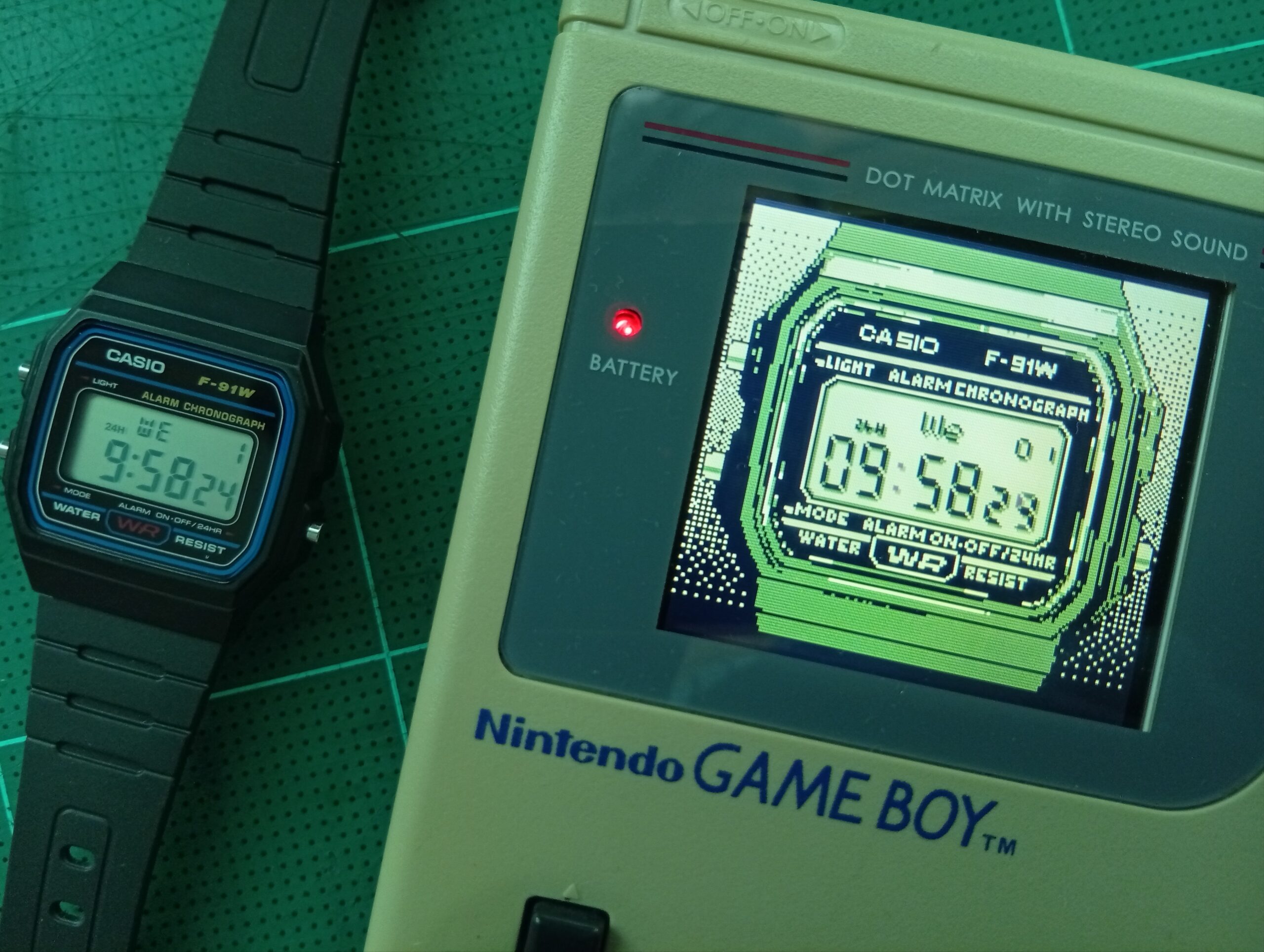

Have you ever thought of turning a Nintendo Game Boy into a digital desk clock? That’s exactly what I did. By combining two of my favorite childhood gadgets—the Game Boy and the Casio F-91W watch—I built a Casio-style clock program using C and GBDK (Game Boy Development Kit).

First Things First

This post won’t cover every single detail—it’s more about sharing my journey, design choices, and the coding challenges I ran into. I’ll walk you through the important parts: graphics, logic, and how I structured the program with a state machine.

Disclaimer

This is a personal passion project. I’m not affiliated with Nintendo or Casio, and the software isn’t commercially available. It’s just something I built for fun out of nostalgia.

Why I started this project?

As a kid, I always wanted a Game Boy but never owned one. Years later, I finally got a few, and instead of just playing games, I thought—why not write my own software for it?

I’ve also always loved the Casio F-91W. It’s such an iconic gadget from the same era. Combining the two felt natural: a Game Boy clock wrapped in the F-91W’s familiar look.

Game Boy basics and limitations

The Game Boy’s screen is tiny—just 160×144 pixels, arranged in 20×18 tiles of 8×8 pixels each. Graphics come in two parts:

- Background → static elements (UI frame, labels).

- Sprites → dynamic elements (digits, icons, blinking cursors).

But there are limits:

- Max 255 background tiles.

- Max 40 sprites total, with no more than 10 per horizontal line.

Sprites are either 8×8 or 8×16 pixels. Bigger objects (like digits) are built from multiple sprites (a “metasprite”).

Because of these limits, I couldn’t rely only on sprites for large digits. Instead, I combined them with a Casio-style frame in the background, which makes the numbers stand out and avoids empty-looking space.

The Game Boy definitely has its quirks, but that’s part of the fun. With a little creativity, there’s always a workaround. So yeah, I could’ve made a simple digital clock that only showed day, date, and digits purely out of sprites. It would’ve worked fine—but with those limits, the numbers would’ve looked tiny and a bit lonely. That’s why I wrapped them in the familiar face of the Casio F-91W. The watch frame doesn’t just “fill the empty space,” it actually makes the time display pop.

The result: a functional Casio F-91W style desk clock running on a Game Boy.

Development Tools & Concepts

- Programming Language: C

- Game Boy SDK: GBDK (a C library with tools for retro game development)

- Graphic Design: Aseprite (a great software for creating pixel arts)

- IDE: Visual Studio Code (one of the best free IDEs for many programming languages)

- State Machine Design Pattern: To systematically manage modes like time-setting, time-keeping, and alarm-setting

- Memory Banking: To switch ROM banks to fit large graphics (or code) into the Game Boy’s limited memory

- Hardware Interrupt: Use Game Boy’s timer interrupt for accurate clock functionality

Features of the Game Boy Desk Clock

The program isn’t just a visual mockup—it works like a real clock. Here are the main features:

- Time Setting – Adjust day, date, hour, and minute.

- Time Keeping – The clock runs in real-time with seconds, minutes, hours, day, and date.

- Alarm Setting – Set an alarm through the time-setting state.

- Hourly Chime – Toggle on/off at any time.

What it doesn’t have (compared to the real F-91W):

- No chronometer/stopwatch. – Essentially, it’s a game console, not a precision watch.

- No 12-hour mode (only 24-hour).

- Not meant to be ultra-accurate—the Game Boy has no RTC.

For a bit of flair, I added blinking behavior to the separator dots.

The Flow of the Program and Button Controls

It’s good practice to plan a program’s flow before coding. Here’s how my desk clock works:

- Time Setting Mode (default on start):

- Select → cycle through fields (day, date, hour, minute).

- Up/Down → change value (wraps around).

- B → toggle hourly chime.

- A → enter Alarm Setting Mode.

- Start → begin timekeeping.

- Alarm Setting Mode:

- Adjust hour/minute like above.

- A cancels, Start saves alarm.

- If alarm already exists, A removes it.

- Time Keeping Mode:

- B toggles chime.

- A removes alarm.

- Select returns to Time Setting.

Under the Hood: Graphics

I designed the layout and digits in Aseprite, then exported them into .c and .h files with a plugin. Have a look at how to install it in Aseprite here.

- Backgrounds → Casio-style watch frame and hour markers (one per hour to respect limits, swapped in with memory banking).

- Sprites → Digits, alarm icon, chime icon, and blinking cursor.

Why no seconds digits? The Game Boy can’t display them cleanly—each digit uses 3×3 tiles, and adding seconds would push some scanlines past the 10-sprite-per-line limit. Instead, I just sync start time with an external clock.

Sprites and backgrounds are kept in arrays and swapped in as time changes. For example, hour backgrounds are stored in an array of 24 and loaded when the hour rolls over.

The display workflow:

- Load background (watch frame).

- Load sprites (digits/icons).

- Position sprites at their coordinates.

This way, only changing parts update each second, while the rest stays fixed.

Adding graphics information to the main code:

#include <gb/gb.h>

#include <stdio.h>

// balnk watch face

#include "blank_bkg_24hr.h"

// sprites, including intro sprites

#include "./trim_sprites/watchface_sprites.h"

// 24HR background data

#include "./background_24hr/watch_face_hr_00.h"

#include "./background_24hr/watch_face_hr_01.h"

...

...

...

#include "./background_24hr/watch_face_hr_22.h"

#include "./background_24hr/watch_face_hr_23.h"Creating array pointers from the included graphics information:

// big number sprite array

const unsigned char *big_num_sprite_data[10][3] = {

{big_0_sprite_tileset_size, big_0_sprite_tileset, big_0_sprite_tilemap},

{big_1_sprite_tileset_size, big_1_sprite_tileset, big_1_sprite_tilemap},

...,

...,

...,

{big_8_sprite_tileset_size, big_8_sprite_tileset, big_8_sprite_tilemap},

{big_9_sprite_tileset_size, big_9_sprite_tileset, big_9_sprite_tilemap}};

// small number sprite array

const unsigned char *small_num_sprite_data[10][3] = {

{small_0_sprite_tileset_size, small_0_sprite_tileset, small_0_sprite_tilemap},

{small_1_sprite_tileset_size, small_1_sprite_tileset, small_1_sprite_tilemap},

...,

...,

...,

{small_8_sprite_tileset_size, small_8_sprite_tileset, small_8_sprite_tilemap},

{small_9_sprite_tileset_size, small_9_sprite_tileset, small_9_sprite_tilemap}};

// background 24hr data

const unsigned char *hr_bg_data[24][3] = {

{watch_face_hr_00_tileset_size, watch_face_hr_00_tileset, watch_face_hr_00_tilemap},

{watch_face_hr_01_tileset_size, watch_face_hr_01_tileset, watch_face_hr_01_tilemap},

...,

...,

...,

{watch_face_hr_22_tileset_size, watch_face_hr_22_tileset, watch_face_hr_22_tilemap},

{watch_face_hr_23_tileset_size, watch_face_hr_23_tileset, watch_face_hr_23_tilemap},

};Load and display background:

// Load and draw initial background

// load background information

set_bkg_data(0, blank_bkg_24hr_tileset_size, blank_bkg_24hr_tileset);

// draw background

set_bkg_tiles(0, 0, 20, 18, blank_bkg_24hr_tilemap);The background information is loaded with the function set_bkg_data(); by setting its first tile at index 0 with the number of tiles and tile information represented by blank_bkg_24hr_tileset_size and blank_bkg_24_hr_tileset. Then, the background is drawn with the function set_bkg_tiles(); starting at tile position x= 0, y = 0 on the 20 x 18 tiles canvas according to the map information represented by blank_bkg_24hr_tilemap.

Similarly the following code snippet show an example of how a sprite is drawn on the screen:

Load and display sprites:

// Load chime and alarm sprite icon information

// Load Chime sprite icon data

set_sprite_data(34, chime_sprite_tileset_size, chime_sprite_tileset);

// Load Alarm sprite icon data

set_sprite_data(35, alarm_sprite_tileset_size, alarm_sprite_tileset); // Alarm

// Display Chime sprite icon data

set_sprite_tile(34, 34);

move_sprite(34, 48, 72);

// Display Alarm sprite icon data

set_sprite_tile(35, 35);

move_sprite(35, 56, 72);set_sprite_tile(34, 34); prepare to show the sprite indexed 34 stored in the VRAM’s tile indexed 34. The function move_sprite(34, 48, 72); shows the sprite indexed 34 at tile position x= 48, y = 72

A helper function to draw a sprite:

Instead of writing two functions consecutively to show sprites on the screen, we can also write up a function that will show any sprites of different sizes at any position on the screen as the following example:

If we want to draw a sprite which occupies 3 x 3 tiles (rows and columns) with the starting sprite index of 8 and starting tile index of 8 at the tile position x = 44 and y = 88, we would used the function above like this: draw_sprite(8, 8, 3, 3, 44, 88);

static void draw_sprite(uint8_t sprite_start, uint8_t tile_start, uint8_t row_tiles, uint8_t, col_tiles, uint8_t x, uint8_t y)

{

uint8_t idx = sprite_start;

uint8_t tile = tile_start;

for (uint8_t row = 0; row != row_tiles; row++)

{

for (uint8_t col = 0; col != col_tiles; col++)

{

set_sprite_tile(idx, tile);

move_sprite(idx, x + (col * 8), y + (row * 8));

idx++;

tile++;

}

}

}

How Backgrounds and Sprites Work Together

Think of the screen as layers:

- Background (Casio frame, labels).

- Sprites (digits, icons, blinking cursor).

- Hardware display blends them together.

This lets me update only what changes (minutes ticking, alarm toggling) without redrawing everything each frame.

Under the Hood: State Machine

I structured the logic with three states:

- Time Setting

- Time Keeping

- Alarm Setting

Each state has its own button mappings and update logic.

// Defining an enumerated data type for time setting

typedef enum {

TIMESET_DAY,

TIMESET_DATE,

TIMESET_HOUR,

TIMESET_MINUTE

} TimeSetField;

// Defining the variable 'timeset_field' with its

// default value

TimeSetField timeset_field = TIMESET_DAY;

// Defining the variable 'joy_read' to get input

uint8_t joy_read = joypad();

// If the 'select' button is pressed, cycle through

// the values in the TimeSetField data type

if (joy_read & J_SELECT) {

timeset_field++;

if (timeset_field > TIMESET_MINUTE) {

timeset_field = TIMESET_DAY;

}

} Timer Accuracy

The Game Boy doesn’t have a built-in RTC, so I used its hardware timer interrupt.

- CPU runs at 4096 Hz.

- An 8-bit counter overflows at 256 (28).

- 4096 / 256 = 16 overflows → 1 second.

I track these overflows with cpu_cyc_count. Each time it reaches 16, one second passes. From there, minutes, hours, days, and dates tick up in the main loop.

// Timer interrupt handler

void timer_isr(void) {

cpu_cyc_count++;

}

void main() {

// Timer ISR initialization

disable_interrupts();

// Timer setup: 16 Hz base

TMA_REG = 0x00; // reload value

TIMA_REG = 0x00; // start from 0

TAC_REG = 0x04; // enable timer,

// input clock = 4096 Hz

add_TIM(timer_isr);

set_interrupts(TIM_IFLAG | VBL_IFLAG);

enable_interrupts();

// Time calculation logic

while (1) {

wait_vbl_done();

// time-keeping

if (cpu_cyc_count >= 16) {

cpu_cyc_count = 0;

sec_count++;

sec_tick = 1;

if (sec_count >= 60) {

sec_count = 0;

min_count++;

min_tick = 1;

if (min_count >= 60) {

min_count = 0;

hr_count++;

hr_tick=1;

if (hr_count >= 24) {

hr_count = 0;

day_count++;

date_count++;

day_tick = 1;

date_tick = 1;

if (day_count >= 7) {

day_count = 0;

}

if (date_count >= 31) {

date_count = 0;

}

}

}

}

}

// The rest of the code...

// The rest of the code...

// The rest of the code...

} // Close the game loop

} // Close main functionThis provides a reliable 1 Hz tick without overloading the CPU.

Extra details:

Blinking Effect → toggle every 20 frames at ~60 FPS.

void main() {

while (1) { // main game loop

wait_vbl_done();

// code ...

// code ...

blink_counter++;

if (blink_counter >= 40) {

blink_counter = 0;

}

// code ...

// code ...

// draw blinking day sprite

// (during time setting):

if (blink_counter >= 20) {

draw_daydate(0, 0, 0, 0);

} else {

draw_daydate(0, 0, 80, 72);

}

// code ...

// code ...

} // close game loop

} // close mainThe Game Boy screen updates at ~59.7 FPS. When the loop is controlled by wait_vbl_done(); The counter (blink_counter) goes up to ~60 at the end of the loop. But this time, we reset it when it reaches 40. The conditional block draws the day sprite while the counter is below 20 and remove it while the counter is above 20. This way, we can create the ‘blinking effect’.

Input Sensitivity → button delay counter prevents “jumpy” input.

void main() {

while(1) {

// code ...

// code ...

// input delay

if (input_delay > 0) input_delay--;

// code ...

// code ...

if (input_delay == 0 && joy_read & J_START) {

input_delay = 12; // reset input delay

game_state = STATE_TIMEKEEPING;

}

// code ...

// code ...

} // close game loop

} // close mainFrom the code above, if the ‘start’ or any button is pressed, the input_delay is reset to 20 and no button can be pressed before it reaches 0 again. Without this mechanism, the button control will be too responsive and feel ‘jumpy’.

What I Learned

Working on this project taught me a lot about:

- Embedded programming concepts with limited hardware.

- Interrupt handling on the Game Boy.

- Using a state machine for clean, scalable game/software design.

- The fun of merging retro hardware with nostalgic design.

Why This Project Matters

For me, this isn’t just about writing code—it’s about connecting with childhood dreams. Owning a Game Boy now and programming it into something unique feels incredibly rewarding. Pairing it with the Casio F-91W aesthetic makes it even more special.

Projects like these are proof that old consoles can be more than just collectibles. They can be platforms for learning, creativity, and fun programming experiments.

Final Thoughts

If you’re into retro programming, C development with GBDK, or simply love the Game Boy as much as I do, I hope this project inspires you to try building something of your own.

Stay tuned—I’ll be posting screenshots, photos of the setup, and snippets of the C code that make this Game Boy desk clock tick.